The Policy of Containment: or How to Trivialize Protests

August 23, 2008

The announcement that outdoor protests will now be allowed in Singapore has so far met with a muted response. No one I know has had anything positive to say about it, be it about the PAP government’s seemingly positive move towards political liberalization or the sudden access to a means of expression that for so long has been rendered alien to so many Singaporeans. Of course the fact that such protests will only be allowed in Speakers Corner (Hong Lim Park) has done much to neutralize any initial euphoria. What do we make of this move by the PAP government?

The announcement that outdoor protests will now be allowed in Singapore has so far met with a muted response. No one I know has had anything positive to say about it, be it about the PAP government’s seemingly positive move towards political liberalization or the sudden access to a means of expression that for so long has been rendered alien to so many Singaporeans. Of course the fact that such protests will only be allowed in Speakers Corner (Hong Lim Park) has done much to neutralize any initial euphoria. What do we make of this move by the PAP government?

First of all, it’s a rational decision given that the ruling against outdoor protests is routinely and nonchalantly flouted anyway by the likes of the Chee siblings, Myanmar students and PRC workers at various spots in Singapore. A ban that is ignored must be re-thought.

Secondly, it is a typical civil servant response to a messy problem. It’s a policy of containment. From a policy maker’s point of view it’s the common sensical thing to do. You have a problem that just won’t go away but it’s one that you do not want to spread. What do you do? You contain it. Just like prostitution and brothels. You’ll never be able to stamp out prostitution so you zone it at red-light districts like Geylang.

Thirdly, by lifting the ban on outdoor protests, the PAP government will now have something to fend off its western critics with. This gesture of liberalization is rather symptomatic of the PAP’s habit of adopting icons from the liberal west and then emptying them of their meaning (We have Speakers’ Corner for free speech but you need to register with the police. We want bohemias in Singapore but we don’t want any deviance.)

All this spells a win-win situation for the PAP government. But it’s bad news for those of us who are serious about the political maturity of Singapore society. This is akin to a surreal cage of freedom where to taste liberty you have to lock yourself in.

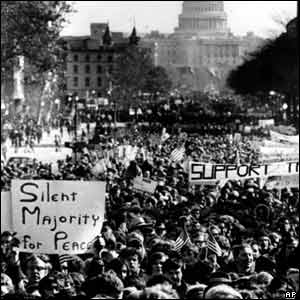

Designating a zone for protest draws an artificial and arbitrary line between everyday life and political expression. It immediately turns the act of public protest into a novelty, a piece of legitimised political entertainment for consumption. The power of public protests comes from its ability to disrupt routine from traffic, to mental to spatial, thus allowing the plight and unhappiness of protesters to register in ordinary citizens who may otherwise be ignorant of their situation. Imagine walking to work from the MRT station and having to move around a group of protesters chanting away. You are suddenly forced to confront the lives and marginalized interests of fellow citizens and, for better or worse, are compelled to listen to them, if only for as long as it takes to wriggle your way through.

Helming in protesters at Speakers Corner takes away the gravity of public protests. There, protests will turn into a spectacle from which the seriousness and gravity of issues are siphoned away because they are removed from the lives of Singaporeans. They become comical events ordinary citizens can take in while sipping coffee or tea from across the road. I would even argue that it’s better not to lift the ban at all because the police and international media would take seriously any protests as long as they remain illegal. At least then the protesters are heard. In the Speakers Corner their newfound legal status may actually silence them.

Putting NParks in charge is no great concession from the government either. There is hardly any difference from having the police circle protesters. All NParks officers need to do is dial 995 and we’re back to square one.

But perhaps most detrimental to our political maturity is the false belief that Singapore really is liberalizing. This nurtures a false sense of achievement or progress. It lulls us into believing that we have arrived at political pluralism and liberalism while distracting us from the array of draconian regulations in place that curb this very pluralism (Newspapers and Printing Press Act; ISA; trade union laws; Electoral Boundaries Committee under the PMO; silencing of the Law Society and so on).

In other words, the lifting of the ban on public protests will serve as a great psychological breakthrough in the minds of ordinary Singaporeans. They will be distracted by the spectacle and believe that they are entering a new phase in local politics. They will, like the PAP government, parade this as a sign of the times, when in fact nothing has changed; at least not for the better.

If the PAP government were really serious it would lift the ban unconditionally and look at the experience of protest coordination in developed countries like the UK. Allow protests to take place anywhere but only after joint coordination between the protest organisers and the police. Both organisers and police have to agree on the estimated number of protesters and the designated area in advance. Organisers should have to put up a modest deposit, a sum that can vary according to the number of protesters expected and the area covered (between $2000-$5000 perhaps). Organisers have to nominate their own monitors (armed with video cameras) who will keep an eye out for trouble makers. After all any self-respecting civil society group wouldn’t want their cause hijacked by others or have their day in the sun turn ugly. Marches can also be accommodated in this manner. The route can be fixed, barracades can be set up to limit public inconvenience and the police can monitor the marches to ensure the interaction between protesters and onlookers does not turn sour.

All this isn’t very hard for the police and the government to do. And it would signal real change.

August 30, 2008 at 2:09 pm

Well argued.

The downside of this change is real.